Imagine, a war-torn world. A young general, Charles de Gaulle, lands in London, escaping a collapsing France. This is the story of his exile, a journey through a city that became his temporary home and a platform for his defiant message.

A New Beginning in London

Charles de Gaulle, a junior minister in a crumbling government and a relatively low-ranking general in a defeated army, arrived at Heston airport in London on June 17th, 1940. Few people recognized him, except for Winston Churchill, who had noticed “a young, energetic general called de Gaulle” during his visits to France.

The next evening, de Gaulle stood at Broadcasting House, ready to record his historic first speech. His powerful words, a call to arms for his countrymen, echoed across the airwaves, challenging the armistice negotiated by the Pétain regime. This act of defiance marked the birth of the Free French movement.

The Free French Find Their Home

For the next three years, London became the nerve center of the Free French. It was here, in the heart of the British capital, that de Gaulle found a haven and established a base for his movement.

Their first temporary headquarters was St Stephen’s House, a building on the Victoria Embankment, known today as Norman Shaw South. Soon, they moved to 4 Carlton Gardens, a building in the neo-classical style, where they remained until 1944.

These buildings hold tangible reminders of de Gaulle’s presence: blue plaques, commemorating his role as President of the French National Committee and the establishment of the Free French Forces headquarters; and a rectangular plaque, inscribed with the inspiring words of de Gaulle’s June 18th Appeal.

A Family’s Journey

De Gaulle’s family joined him in London shortly after his arrival. They had endured a harrowing journey by sea from Brest to Plymouth. Reunited at the Rubens Hotel in Buckingham Palace Road, the family experienced a moment of joy and relief, a rare glimpse of normalcy amidst the turmoil.

The de Gaulle family settled in Birchwood Road, Petts Wood, allowing de Gaulle to commute to Carlton Gardens. However, the area’s proximity to the war’s frontlines proved unsettling, especially for young Anne de Gaulle, who had Down’s syndrome.

This led to a series of moves, first to a house in Shropshire, then to Little Gaddesden, Hertfordshire, where de Gaulle could spend weekends with his family. During the week, he resided at the Connaught Hotel in London.

Finally, in September 1942, the family found a permanent home in London at 99 Frognal, Hampstead. De Gaulle’s Catholic faith led him to regularly attend mass at St. Mary’s Church, a church built for French Catholic émigrés.

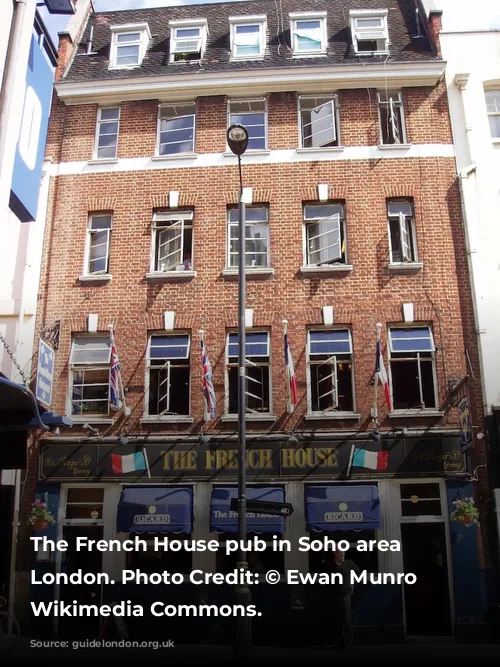

Soho: A Haven for the Free French

London’s Soho district has long been a haven for French émigrés. This vibrant neighborhood provided a sense of community and familiarity for the Free French, who spent their off-duty hours in its shops, restaurants, and pubs.

The French House, a pub previously known as the York Minster, stands as a testament to the Free French presence in Soho. It holds a special place in their memory, a reminder of the camaraderie and resilience they found in this corner of London.

A General’s London

De Gaulle, though often found in the heart of London’s social scene, preferred the Connaught Hotel for his meals, sometimes dining in a Pall Mall club or a celebrated French restaurant like the Coq d’Or or the Savoy. He understood the importance of the “working lunch” in British society and used this opportunity to discuss the war, the future of France, and the Anglo-French relationship, often conducting these discussions in French.

His towering figure, in the familiar uniform of a French officer, was a familiar sight as he walked from Carlton Gardens to the Connaught for lunch. Despite his complex relationship with the British government, Londoners welcomed him warmly, recognizing his dedication to the cause of freedom.

De Gaulle’s Mark on London

Many of London’s most iconic buildings hold memories of de Gaulle’s time in the city. He addressed assemblies of the Free French community at the Albert Hall, his speeches included in the daily broadcasts to occupied France. He also spoke to members of the Lords and Commons at the Houses of Parliament, delivering his message in English.

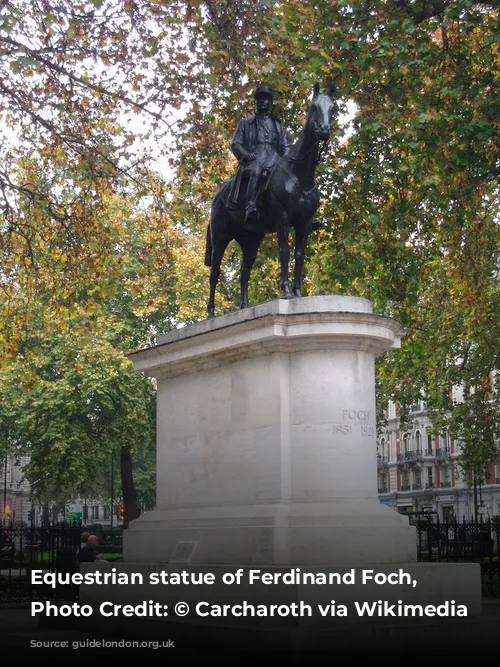

The statue of Marshal Foch in Grosvenor Gardens became a rallying point for the Free French, where they held regular parades on Bastille Day, with de Gaulle laying a wreath in honor of the former Commander-in-chief.

A Return as President

In 1960, de Gaulle returned to London, this time as President of the French Republic, for a state visit. This visit, at a delicate time in Franco-British relations, was a reminder of the complex ties between the two nations.

De Gaulle, accompanied by the Queen, rode in an open carriage to Buckingham Palace. He attended a gala ballet performance at Covent Garden, visited the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, and addressed the Houses of Parliament in French, at a ceremony in Westminster Hall, with a military band playing in the background.

The highlight of his visit was a full-scale review of the Household Brigade at Horse Guards, a rare honor reserved for foreign heads of state. De Gaulle, in the uniform of a général de brigade, rode down the Mall in an open carriage, accompanied by Prince Philip, who also wore a brigadier’s uniform in his guest’s honor. As the carriage passed Carlton Gardens, de Gaulle saluted his old comrades with a solemn gesture.

London echoes with Charles de Gaulle’s legacy. The city witnessed his defiant struggle, provided a refuge for his movement, and played a key role in shaping the future of France. His story lives on in the streets of London, a testament to a man who, in a time of darkness, brought hope and inspiration to a nation fighting for its freedom.